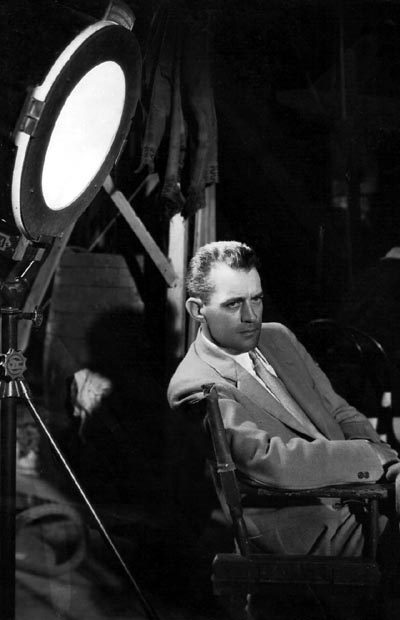

W.S. Van Dyke

DirectorBiografía

For the better part of his career, Woodbridge Strong Van Dyke lived up to his sobriquet “One-Take Woody” by steadfastly adhering to his credo of shooting each scene as quickly and efficiently as possible. Over his 25-year career, he economically directed over 90 diverse entertainments, which not only saved the studios vast amounts of money but turned out to be some of the most interesting motion pictures created during this period. Van Dyke’s father, a lawyer, died within days of his birth. By the time he was three Woody and his mother were forced to tread the boards of repertory theatre to make a living. When he hit his teens he had a succession of outdoor jobs, including lumberjack, gold prospector, railroad man and even mercenary. In 1916 he was hired by the legendary D.W. Griffith as one of a group of “assistants” (others included Erich von Stroheim and Tod Browning) to work on the picture Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages (1916). After that, his rise was truly meteoric. Within a year Woody was directing his own films, beginning with The Land of Long Shadows (1917). A later western, The Lady of the Dugout (1918), featured a ‘genuine’ former Wild West outlaw, the self-promoting teller of tall tales, Al J. Jennings. After enlistment in World War I, Woody returned to Hollywood in the 1920s to direct further westerns, beginning with some Gilbert M. ‘Broncho Billy’ Anderson features at Essanay and later Tim McCoy programmers (once, in 1926, he directed two features simultaneously). Woody was perhaps the first filmmaker to make westerns that strayed from the stereotypical jaundiced pro-white man view in favor of a more sympathetic portrayal of the American Indian on screen. Woody’s “One-Take” nickname came about as a result of filming world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey in Daredevil Jack (1920). Dempsey invariably flattened his opponents with the first punch, so it became imperative to have the scene “in the can” on the first take. As a result, Woody was much in demand throughout the decade for “quota quickie” westerns and serials. Under contract to MGM in 1928, he accompanied documentary filmmaker Robert J. Flaherty to Polynesia to collaborate on the feature White Shadows in the South Seas (1928), taking over direction entirely when Flaherty fell ill. The success of the picture led to the thematically similar The Pagan (1929), shot in Tahiti with Ramon Novarro. This was in turn followed by the epic Trader Horn (1931), filmed on location in remote parts of Kenya and Tanganyika. Driven to the point of physical exhaustion by the swashbuckling director, the 200-strong crew virtually transformed the wilderness, creating, as it were, a live set, replete with exotic animals and plant life to capture unprecedented footage. In fact, there was so much excess footage after release of “Trader Horn” that much of it was incorporated into Woody’s next project, the seminal Tarzan the Ape Man (1932), which set the bar for later entries into the Edgar Rice Burroughs cycle. After another flirt with danger, filming Eskimo (1933) in the remote Bering Strait, Woody settled down to less life-threatening assignments. During the next few years, Woody Van Dyke showed his remarkable flair and versatility. After being Oscar-nominated for The Prizefighter and the Lady (1933), he directed William Powell and Myrna Loy in their first outing together in Manhattan Melodrama (1934) (most famous as the film seen by infamous bank robber and killer John Dillinger just before he was shot to death by the FBIl). He followed this with the stylish and witty thriller The Thin Man (1934) (filmed in true Woody-style in 16 days) and its three sequels, teaming Powell and Loy in one of Hollywood’s most successful partnerships. After these hugely popular movies, Woody proved to be equally adept at musicals, directing yet another dynamic duo, Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, in the operettas Rose-Marie (1936), Sweethearts (1938) and Naughty Marietta (1935). Never turning down an assignment, he also handled family fare (Andy Hardy, Dr.Kildare), social (The Devil Is a Sissy (1936)) and historical dramas (the lavish Marie Antoinette (1938) with Norma Shearer). Unquestionably, one of the highlights of Van Dyke’s career as a director was the first true “disaster movie”, San Francisco (1936), for which he elicited rich, natural characterizations from his cast for 97 minutes. He then re-created the 1906 earthquake in the remaining 20-minute finale, achieving a realism that has rarely been matched and never surpassed. He was nominated for Academy Awards for both “The Thin Man” and “San Francisco”, but lost out on both occasions. A colorful, larger-than-life character, his “shoot-from-the-hip” camera style was at times criticized by his peers. Conversely, he was much respected by actors, frequently giving breaks to unemployed performers by using them in his films, and appreciated by the studios by consistently coming in on or under budget. In addition, he was known as a “film doctor”, who would be called upon to re-shoot individual scenes with which the studio was dissatisfied (a noted example being for The Prisoner of Zenda (1937)), or, alternatively, to shoot additional scenes that were deemed necessary for continuity. Like some of his peers, Woody could be an autocrat who rarely brooked arguments and was known to greet the mighty Louis B. Mayer himself with “Hi, kid”. He became ill during the filming of Dragon Seed (1944). Diagnosed with heart disease and cancer, he committed suicide in February 1943.